What Banned Books Week, 40 Years After Its Founding, Means for Seattle Readers

Banned Books Week, in its 4oth year, is the American Library Association’s annual rallying cry for resistance to censorship. It was launched in 1982, when a rising tide of attempts to remove books from libraries had the ALA clamoring for the public’s attention.

Now we’re experiencing another, even bigger surge of attempted book bans around the country. And Seattle Public Library regional manager and intellectual freedom expert Steve DelVecchio points out that a striking majority of these would-be restrictions target the work of Black and LGBTQ authors.

Ensconced within the liberal bubble of Seattle, it’s tempting to deem these issues peripheral, or even assume that being banned in some more conservative place might actually provide titles with a bit of free press. As said literary works make headlines, librarians and booksellers around the country rush to their defense.

But DelVecchio insists that “ultimately, it’s still very dangerous” to let any attempts to ban titles go unchallenged, and that people with the fewest economic and educational resources are the ones most “at risk of not having access” to these books should attempts to suppress them prove successful. We’re not absolved of concern, just because some of SPL’s most popular titles are ones that have also been challenged in libraries elsewhere.

DelVecchio stresses that this is not a partisan issue. He points to a survey conducted this year on behalf of the ALA, which finds that the majority of Americans oppose book bans—across the political spectrum. While high-profile attacks on books are overwhelmingly motivated by content objectionable to conservatives, like overt discussions of race or the LGBTQ experience (see: Big Wig), 70 percent of Republicans surveyed said they opposed efforts to have books removed from their local libraries.

Ghost Boys author Jewell Parker Rhodes.

In January of this year, the Mukilteo School Board drew national scrutiny for its decision to remove Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird from the required reading list. School board president Michael Simmons expressed frustration that the media narrative, in certain instances, lumped this decision together with the troubling proliferation of book bans. “It almost felt like people were attacked personally by the fact that we were considering the step that we took,” says Simmons. While the novel has faced many challenges since its publication in 1960, this was not exactly that.

The school board, after much deliberation, elected to no longer require that teachers include the book in their syllabus, in part to make room for more contemporary works by authors of color. Removing the book from the library was never on the table, stresses Simmons.

The school board’s reassessment of the title’s place in the curriculum, in spite of its status as a sanctified classic, and the ensuing backlash, are a lesson in nuance. This is not an issue that falls neatly on either side of political lines, and just because a title has been challenged doesn’t mean it ought to be uncritically embraced in perpetuity. It’s up to us to read and decide for ourselves, and to defend our right to do so.

Banned and Challenged Books Recommended by the SPL

Bless me, Ultima by Rudolfo Anaya

Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story by Kevin Noble Maillard

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie

An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros

Always Running: La Vida Loca, Gang Days in LA by Luis J. Rodriguez

House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende

Our picks from Pacific Northwest Authors

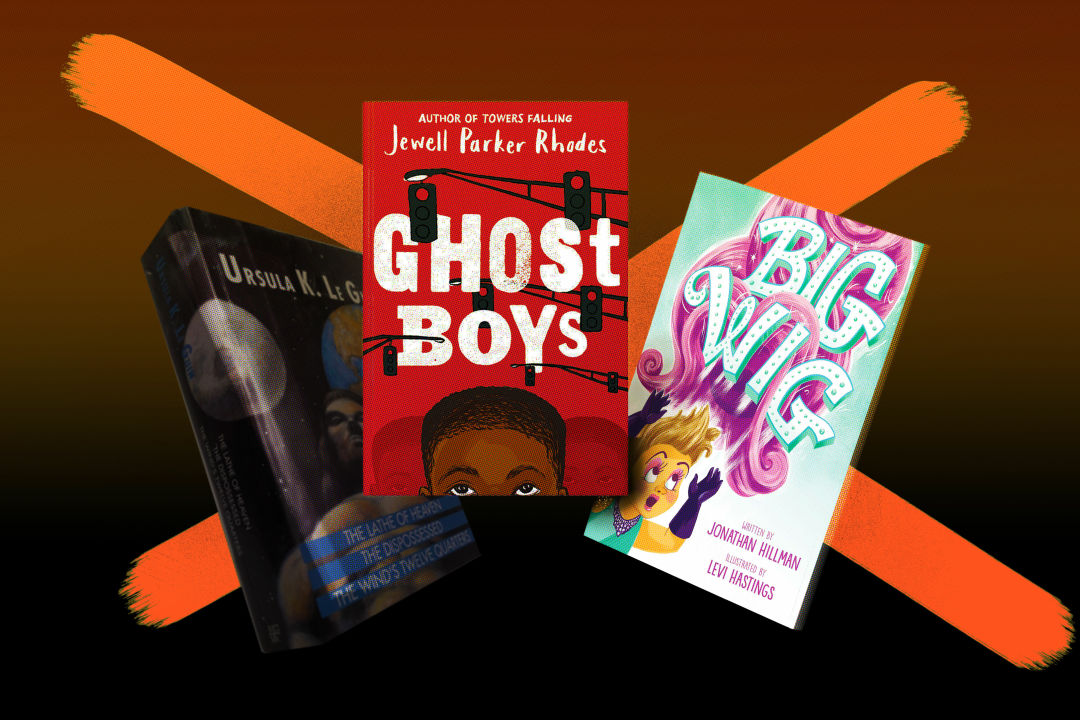

The Lathe of Heaven by Ursula K. Le Guin

Ghost Boys by Jewell Parker Rhodes

Big Wig by Jonathan Hillman and Levi Hastings