Scents from a Mall: The Sticky, Untold Story of Cinnabon

A cook called in sick. The kitchen was beyond slammed. And, naturally, the phone was ringing. The restaurant’s proprietress barely answered in time. But she knew the voice on the line, though mostly by reputation within Seattle’s small food community. Rich Komen cut to the chase: “Hey Jerilyn, how’d you like to make the world’s greatest cinnamon roll?”

The year was 1985, and Jerilyn Brusseau had built a reputation of her own over the years. She sourced the ingredients for her eponymous restaurant in Edmonds, just north of Seattle, the way she’d learned on her parents’ dairy farm—from the people who grow them. Her VW bus crisscrossed the Snohomish, Skagit, and Whatcom Valleys to collect salad greens, shellfish, and 300 pounds of unsalted butter made every other week just for Brusseau’s. A few months before the phone rang, The New York Times had included Jerilyn in a lengthy, photo-splashed write-up about this revolutionary idea of eating local.

There was another reason she was on Rich Komen’s mind. Jerilyn Brusseau grew up making cinnamon rolls with her grandmother, who baked pies for the restaurants in her small Montana town. When Jerilyn and her then husband transformed a former Shell station—piles of rubble out front, windows blackened over with gunpowder from a stint as a firearms shop—into Brusseau’s in 1978, she originally feared her grandmother’s cinnamon rolls would seem too ordinary among the croissants and danishes and brioche. However those “ordinary” fragrant pinwheels of dough and dark, sticky filling built a fan base that stretched down to Seattle.

When she picked up the phone that day, she had no idea this mysterious cinnamon roll project would ultimately become a national brand with 1,200 franchised locations in 48 countries. Or that people would still ask her for autographs and photos nearly four decades later. She just knew that when a guy like Rich Komen calls—someone who had already opened multiple successful restaurants in Seattle and various far-flung states—you simply say, “Great, let’s do it.”

Today, Cinnabon is headquartered in Atlanta, its Seattle origins now melted into the crevices of its history. But this singular product of 1980s mall culture sprang to life in a test kitchen across the street from Gas Works Park. Its unrepentant decadence remains lodged in our psyche; its relevancy has outlasted arguably less crave-inducing (if equally nutritionally dubious) food court contemporaries like Sbarro or Panda Express or TCBY.

That’s probably why comedians love to riff on Cinnabon. In one of his bits, Louis CK describes it as “a six-foot-high, cinnamon-swirled cake made for one sad, fat man”—meaning, of course, himself. Conan O’Brien doesn’t even need a punch line; he merely says the word Cinnabon and the crowd cracks up. And, of course, there’s Breaking Bad. On the penultimate episode of the AMC series, flamboyantly corrupt attorney Saul Goodman contemplates the unspectacular life he’ll lead if he assumes a new identity: “If I’m lucky, a month from now, best-case scenario, I’m managing a Cinnabon in Omaha.” It’s an offhand line (though carefully vetted in the writers’ room) that later acquires unexpected significance in the show’s spin-off, Better Call Saul. Cinnabon’s moment of modern-day TV fame even has a behind-the-scenes Seattle connection.

Cinnabon was intended to be a national chain, even before the first customers lined up to sample the cinnamon rolls, a recipe Jerilyn Brusseau refined and refined until it finally reached the superlative heights Rich Komen envisioned when he placed that call. On opening day, a pink neon sign touted “World Famous Cinnamon Rolls,” an absurd boast for a brand with one location in a second-tier mall outside Seattle. Except, it would eventually come true.

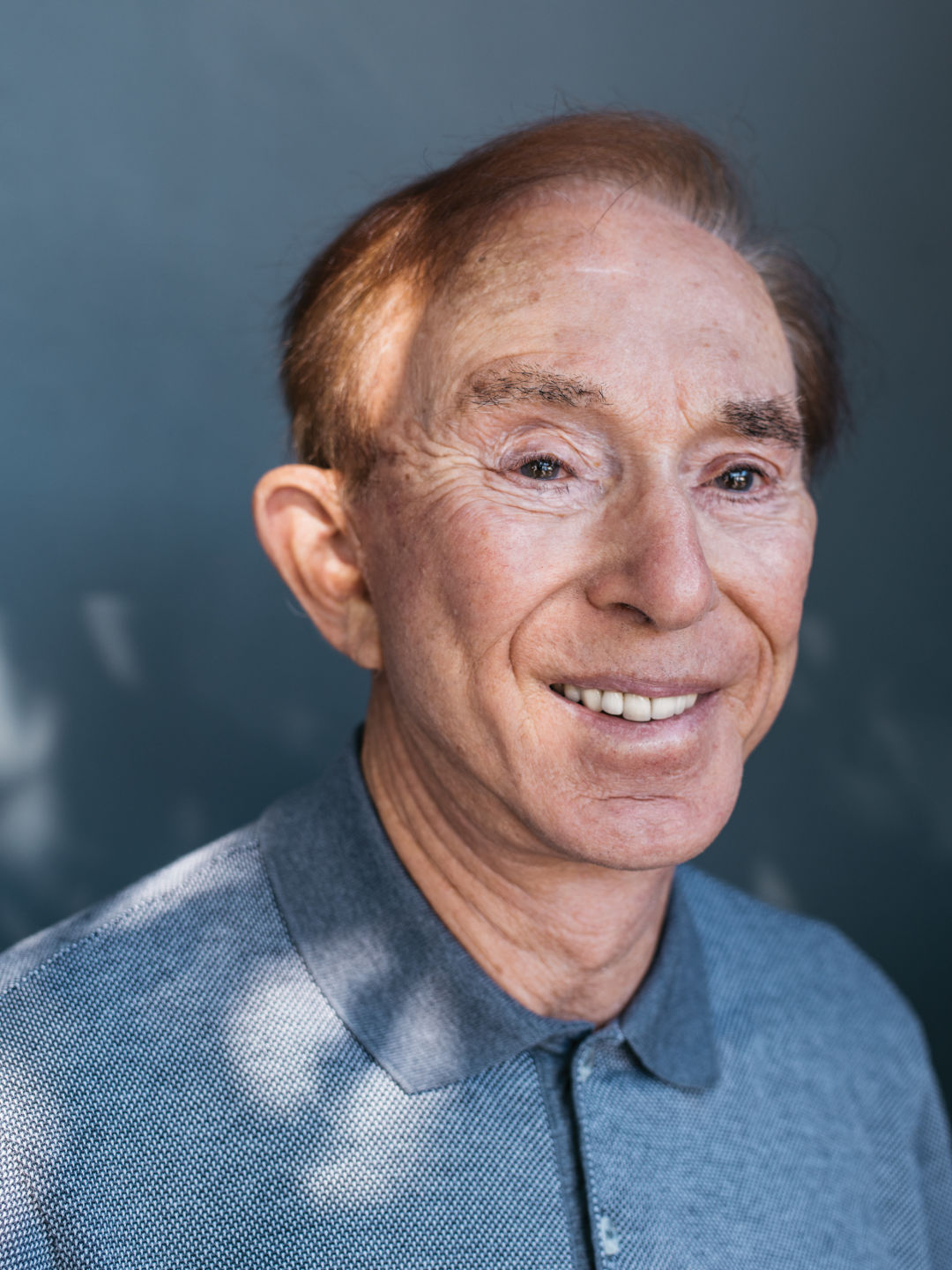

Jerilyn Brusseau helped craft the original Cinnabon recipe in 1985.

Image: Kyle Johnson

The aroma assailed Rich Komen the moment he stepped inside Ward Parkway Shopping Center in Kansas City. The restaurateur had flown in from Seattle that winter morning in the final days of 1984 to follow a tip. Now he was following the smell of butter and cinnamon.

Pervasive though it was, Rich couldn’t find the source. Finally, he descended to the lower level. The restaurant industry veteran gasped involuntarily: “It was the worst location in the mall,” he remembers. A counter snugged between the up and down escalators. Rich didn’t yet know the owners had designed its open ceiling to ensure the smell of baking would permeate the air. All he knew was, “There were 22 people standing in line to buy these darn cinnamon rolls.”

Slight of stature but mighty in reputation, Rich Komen was in his early 50s. Thirty years earlier, he was just a guy with a bread and dairy merchandising job, $1,000 in savings, and some frustrations about the hot dogs his beloved alma mater, the University of Washington, served at football games. Despite possessing zero dining service experience, he bid on and won the contract to run concessions at Husky Stadium. That led to a contract to serve food at Seattle Center, a new complex built for the 1962 World’s Fair. Soon he was handling concessions at two ski resorts, the Oakland Coliseum, and Kansas City’s Harry S. Truman Sports Complex, where the Chiefs and the Royals play.

By the time he prowled Ward Parkway Shopping Center’s wide indoor avenues in 1984, his company, Restaurants Unlimited, had five full-service establishments around Washington and as far away as Hawaii and Illinois. A friend from Rich’s Kansas City days had called with some intriguing intel: A local outfit called T. J. Cinnamons had graduated from a mobile bakery that served fairs and carnivals to a spot at the mall. And wow, were people into it.

T. J. Cinnamons served just one item—cinnamon rolls the size of a softball. This simplicity appealed to a guy who built his career on stadium concessions. The trend-spotting side of Rich Komen also took note that shopping malls had evolved from mere retail hubs geared toward car-dependent customers to social enclaves where teenagers hung out and chain stores spread a commonality of culture from high-tops to hair gel to Madonna cassettes. All this shopping and scene-making worked up an appetite; the mall had also become a place to eat.

Rich wanted to franchise T. J. Cinnamons on the West Coast, but the owners would only grant him the rights to Washington. Fortunately he’d done his homework and sussed out the Idaho bakery where T. J. Cinnamons got its idea. But after a few conversations with Mrs. Powell’s, whose cinnamon rolls were the talk of Idaho Falls, that franchising deal fell through, too. Rich had been so confident he’d already leased his first location in SeaTac Mall, 20 miles south of Seattle, in the town now known as Federal Way. By the summer of 1985, he had no cinnamon rolls, but a legally binding agreement to open a cinnamon roll counter that December. “Okay,” he told himself. “We’ll invent our own concept.”

Jerilyn Brusseau reported to the Restaurants Unlimited test kitchen on Northlake Way in late August, just three months before the rolls were supposed to debut. Rich brought in proofers and a 20-quart mixer. He ordered up a sign with just one word, in letters eight inches high: “Irresistible.”

Years later, he would recall that this nebulous yet knowable sensation was the only mandatory aspect of his dream cinnamon roll. But there were a few other requirements. A lemony cream cheese icing like the one from Mrs. Powell’s. These new rolls should also be enormous, worth the then-hefty $1.25 price tag, and deliver what Rich termed “a big cinnamon hit.” Freshly baked was a must, though a brief stay on a hot plate was permissible. A more prosaic nonnegotiable: Rolls had to bake in 14 minutes in a convection oven. His concession days taught him this was the longest someone would wait in line. Jerilyn’s famed rolls usually took about half an hour.

Assisting Jerilyn was Rich’s son, Greg. The younger Komen was a year out of college and managing the bar at Cutters, Restaurants Unlimited’s property overlooking Elliott Bay. He knew nothing about cinnamon rolls, but he did know the path to management in his dad’s company involved years of working his way up. This cinnamon roll thing felt more entrepreneurial, more fast-tracked. Maybe it wouldn’t pan out to more than a few locations. Then again, “Heck, it could be the next Mrs. Fields.”

Jerilyn’s luminous blue eyes radiate the same comforting warmth as her baked goods; this serene aura would come in handy in the intensive weeks to come. In the test kitchen, she might bake four batches in a single morning. She’d roll out the dough and push softened butter over it to form a thick layer. Then came a mix of brown sugar and cinnamon, not scattered daintily, but applied so thickly the opaque russet-colored layer almost resembled pizza sauce. Greg was by her side to roll, learn, and heft the big bags of flour.

The first order of business was perfecting a dough both pillowy and able to hold its shape. When rolls came out of the oven, Rich would descend from his third-floor office and thoughtfully chew one while a roomful of people watched. “I learned to fail exceedingly well,” Jerilyn remembers.

Batch after batch. Rejection after rejection. “I can’t tell you how many times I tried something and said, ‘This is fantastic!’” Greg remembers. “Dad would come in and spit it out.” Always with insightful commentary, of course.

Rich Komen was already a successful local and national restaurateur when he started Cinnabon in the 1980s.

Image: Kyle Johnson

A major breakthrough came courtesy of their spice supplier, who pointed out that cinnamon isn’t just cinnamon. Like wine or coffee, there are different varieties, and cinnamon from different regions, even different elevations, yield their own distinct flavors. Rich asked a rep to school the group on this seemingly innocuous baking spice. They landed on Korintje cinnamon, harvested from the bark of trees that grow at very high elevations in Sumatra. It delivers cinnamon’s familiar punch, but tends toward the sweet and amiable, rather than that devilish bite that punctuates red hots or schnapps.

Here, at last, was Rich Komen’s elusive cinnamon hit.

In the oven, that lavishly applied layer of butter, cinnamon, and brown sugar would meld into a sticky-sweet syrup, known in official Restaurants Unlimited parlance, as goo. It’s central to a cinnamon roll’s appeal, but the stuff kept sliding out from the spiral folds of dough to pool in the bottom of the custom-size baking pans Rich had commissioned. By November, Jerilyn had conquered this setback and the recipe was almost there.

But, irresistible? Not just yet. The rolls remained a little dry for Rich’s taste, and opening day was in less than two weeks. By then Greg had absorbed enough lessons working alongside Jerilyn, who’d returned to Brusseau’s, to make one final but critical adjustment. A trained baker will pull rolls from the oven when they hit 190 degrees. An internal temp of 165 might scandalize purists, but kept the rolls slightly doughy in the middle. Greg describes it as “medium rare to even rare,” not unlike a steak. At last, a cinnamon roll worthy of his father’s test kitchen sign.

On December 4, 1985, there were no tweets or icing-laden Instagram posts to herald Cinnabon’s arrival. Greg Komen and his crew simply opened the register and started baking. The perfume of butter and cinnamon, plus a few rounds of free samples, did the rest.

Higher-end malls in the region, like Northgate and Bellevue Square, passed on Rich Komen’s untested concept once they heard it only sold one item. But at sleepier SeaTac Mall, the new bakery’s striped awnings and blue-and-white-tile facade scored prime real estate right at the entrance of the food court. The unusual three-sided stall practically demanded that passing holiday shoppers stop in their tracks to watch employees mix and roll dough or apply lascivious amounts of frosting to the finished product, all behind a glass partition designed precisely for its audience-luring capabilities.

Cinnabon did an impressive $500 in sales, then doubled that number the next day. An order was placed for a second dough proofer. In the first few weeks, Cinnabon had raisins. The younger Komen, now the bakery’s manager, soon realized how deeply—deeply—divisive these can be. He told his crew to yank the raisins from the recipe his father had vetted so carefully.

A month in, Greg hired a woman 10 years his senior to be his replacement. He’d known her when they both worked at Cutters, his father’s restaurant down by Pike Place Market.

Sunny and gregarious, Debbie Rowley reported to the new bakery in the white blouse and goofy black necktie required of Cinnabon employees so Greg could depart to open the second location, already in the works in Las Vegas. Next he’d turn his attention to six more Cinnabons due in the following year, from Yakima to Santa Rosa, California, including Bellevue Square and Northgate Malls, which quickly came around once their owners saw some sales figures.

From the company’s earliest days, many fans have pronounced its name as “Cinnabun.” It’s a natural inclination, but one originally rejected by Seattle’s resident branding genius, the guy Rich Komen hired to name his cinnamon roll shop. Terry Heckler created the sort of TV spots that lodge themselves in the regional consciousness: zoomorphic Rainier Beer bottles scuttling about on two legs; a motorcycle roaring down a country road, its shifting gears growling out “Raaaiiiinieeeer Beeer.” Heckler also reportedly advised the founders of a small local coffee company that brand names beginning with St were particularly powerful; later he doodled a logo for that same little coffee company—a long-haired mermaid with a crown, double tail, and a siren’s knowing smile.

He didn’t want bun in the name, since that word implies savory, bready things rather than frosted indulgence (fair point, plus the word’s secondary associations range from butts to ballerinas to expectant mothers).

Instead he turned his thoughts to another decadent pleasure, the bonbon. It connotes something sweet, Heckler explains, “and holy smokes, it really gets you smiling.” If you really wanted to get sophisticated about it, Heckler notes, bon is also French for “good.” Long after Cinnabon’s first location grew into a national phenomenon, Heckler’s creation would also break bad.

Debbie Rowley ran the first Cinnabon at the mall now known as the Commons at Federal Way.

Image: Courtesy Debbie Rowley

Late one June night in 2014, a film crew descended upon Albuquerque’s Cottonwood Mall to transform its Cinnabon into a tiny slice of Omaha, complete with a food safety certificate from the Omaha health department.

Amidst actual Cinnabon employees stood actor Bob Odenkirk, almost unrecognizable, thanks to a droopy mustache, thinning hair, and woefully dorky glasses. Along with his Cinnabon visor he wore a Cinnabon apron, and a Cinnabon name tag: “Gene/Manager.” In the very first episode of Breaking Bad’s spin-off, Better Call Saul, his character’s dire prediction of life under an assumed identity has come to pass.

In the premiere, an overhead shot frames Odenkirk’s actual hands (he declined Cinnabon’s offer of a hand double) as he rolls dough and spreads those familiar thick layers of butter, then cinnamon and brown sugar. If Breaking Bad dedicated montages to the poetry of cooking meth, the opening scene of its spin-off found a similar nexus of art and chemistry in making a cinnamon roll.

Sitting off camera, tickled as hell to be in her own director’s chair, was Debbie Rowley, the woman Greg Komen had hired three decades earlier to manage that first bakery. By then, she was a VP of operations for Cinnabon, still living in Seattle’s Queen Anne neighborhood—and a Breaking Bad superfan. She was downright giddy when that show originally referenced her longtime employer and happened to be at the Atlanta headquarters when a rep from Better Call Saul inquired about shooting a scene at an actual Cinnabon.

From a marketing standpoint, when a show that centers on making meth name-checks your brand to invoke the most unimpressive, banal life imaginable, what do you do? If you’re Cinnabon, you embrace it without reservation and enjoy the attendant publicity.

It would’ve made sense for the corporate office to send the training manager. “No fricking way,” Rowley told her boss. “This is mine.”

She flew to Albuquerque and schooled Odenkirk in the kitchen of the local Cinnabon after it closed for the night. He learned how to mix dough and frosting, how to roll, and even how to cashier. Rowley reviewed the script in advance to ensure characters followed proper Cinnabon protocol, like checking the temperature of rolls fresh out of the oven before you frost them. She even donned a plaid jacket and hat to score screen time as an extra, a woman standing out in the mall.

Cinnabon is a “wonderful word,” notes Peter Gould, cocreator of Better Call Saul, starring Bob Odenkirk (pictured here).

Three years in, fans of Better Call Saul now know each season begins with a black-and-white montage of protagonist Saul Goodman’s new life as Gene the sad-sack Cinnabon manager before it shifts back to the past. Cinnabon’s original spotlight in Breaking Bad was merely a passing comment, but “There’s something fun about seeing a piece of dialogue like that come true,” says Peter Gould, who wrote and directed for Breaking Bad and cocreated Better Call Saul. Of course, none of this would have happened if Breaking Bad had stuck to its original script, in which Saul Goodman’s fate was perhaps even more dire: “Best-case scenario, six months from now I’m managing a Hot Topic in Omaha.”

When the showrunners discovered that this teen clothing chain, with its heavily branded T-shirts and tchotchkes, sold Breaking Bad merchandise, it seemed unsavory to hawk their own wares in this fictional world, even indirectly. They reverted to another idea from a previous conversation. “I will say, Cinnabon was my personal favorite,” recalls Gould. “It’s a wonderful word to say.”

Both brands, Gould notes, conjure up deep associations with malls. But how fitting that a show rooted in the unlikely levity of making and dealing drugs forged this creative partnership with another concoction that people have trouble resisting.

There’s a distinct sound when a mall opens in the morning, the soft clank of gates rolled up to greet the day. At Bellevue Square it begins at 9:29am. On this particular morning, Paula Abdul’s “Forever Your Girl” floats across the three-level atrium as elevators glide up and down their glass shaft. Two ladies in white tennis shoes beat a slow and steady path past the Coach store. It could easily be the late ’80s; only the sound of espresso machines at the Beecher’s–Caffe Vita counter (a nod to malls’ current pendulum swing back to local restaurant brands) places this moment in 2017.

Just around the corner, Greg Komen places his usual order—minibon with extra icing and a coffee—at the Cinnabon. It’s one of the eight locations he cherry-picked to keep when his dad sold the company. Over his shoulder you can see the enormous mixer and dough proofing in the oven; Greg’s locations still make their rolls from scratch (well, technically a base mix), while most franchises’ rolls begin with sheets of frozen dough.

At 55, Greg is still a charismatic advocate for the brand. Not that he’s a carbon copy of his dad. Greg is much taller, and as energetic as Rich Komen is understated. His flashing smile and expressive face suggest a trim, restrained Jim Carrey. But he has his own instinctive understanding of the psychology that underpins the appeal of his father’s decadent creation.

If Cinnabon could go gangbusters at a quiet mall like SeaTac, Greg remembers, the Restaurants Unlimited team figured it could succeed anywhere. When stores in more desirable locations struggled, the team learned a real estate lesson that doubled as a fundamental truth about Cinnabon itself: People don’t eat these doughy spectacles because they want to. They eat them because they lack the strength to resist. The wafting scent that caught Rich Komen’s attention back in Kansas City is a straight-up business tool, and the original Cinnabon’s high-visibility location was key to its success. “Let’s face it, people really want to avoid us,” Greg told an audience during a speech at Zillow a few years back. “We have to get in your way!”

Cinnamon roll scion Greg Komen still owns eight locations of the iconic mall fixture his father founded, including in Bellevue Square.

Image: Kyle Johnson

The company anticipated mega sales when it opened bakeries in a handful of Seattle-area QFCs in 1996. Instead, remembers Greg, “We’d get a three-month boost, and sales would just die.” In marketing speak, Cinnabon suffers from high levels of “product fatigue.” In real talk, it’s not the type of thing most people can eat on a regular basis and maintain their self-respect—or their pant size. Grocery store regulars eventually learn to resist the siren song of icing, dough, and cinnamon goo.

Malls, by contrast, offer a concentration of people who return less frequently. So does the humanity-packed portal that’s been Cinnabon’s other natural habitat since the early ’90s: the airport. It’s a similarly scent-trapping enclosed space, plus people tend to set aside their usual nutritional mores when traveling.

“For so many years, everyone was so insecure about being a freaking indulgent calorie bomb,” says Greg. “The best thing this company ever did is not be insecure about what we are.”

By 1998, Rich Komen was focused on other projects and ready to sell Cinnabon. The company’s next owner, AFC, opened locations outside North America, lending belated credence to that claim of “World Famous Cinnamon Rolls.” Its current owner, Focus Brands, makes more money selling them through other restaurants and licensing Cinnabon-branded cereal, coffee creamer, even candy canes than it does on the bakeries.

Today, Cinnabon is headquartered across the country from its former home on Lake Union; the original location in SeaTac Mall, which is now known as the Commons at Federal Way, closed a decade ago. Debbie Rowley, the bakery manager turned Bob Odenkirk’s personal Cinnabon trainer, retired in 2016, after 30 years with Cinnabon. Greg headed up the effort to surprise her with a custom ring, set with pavé diamonds swirled like a cinnamon roll.

Jerilyn Brusseau, the woman behind that willpower-proof recipe, never stopped connecting people via her food. She led culinary diplomacy exchanges; she baked cinnamon rolls in the Soviet Union, in hopes their enjoyment might inspire common ground. After she sold Brusseau’s, she and her second husband, Danaan Parry, founded a humanitarian program called PeaceTrees, which removes land mines in Vietnam and plants life-affirming trees in their stead.

She still uses her gram’s recipe to make cinnamon rolls for special people in her life: Her six grandchildren. Her teammates for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society’s annual run. The ferry captain on her Bainbridge-to-Seattle route whom she’s known ever since that horrific November day in 1996, when he held her hand and took care of her car after Danaan collapsed and died of a heart attack on the ferry gangway and Jerilyn was already aboard.

Cinnabon still calls Jerilyn for the occasional TV appearance; she’s become the confection’s wholesome origin story and even has an official nickname, Cinnamom. In all these years, she hasn’t grown weary of her association with cinnamon rolls: “Never, they have so much magic in them.”

For the fictional Saul Goodman, these pastries literally offered a new life; for Jerilyn Brusseau, they form a common link through love, tragedy, a quirky sort of fame, and the unexpected directions life takes you. Predicting any of these things is about as futile as trying to resist the aroma of a cinnamon roll, still warm from the oven.