Tahiti Might Be the Hawai'i Alternative Seattle Needs

The view from Moorea's Three Coconuts Lookout captures French Polynesia's lush island vibe.

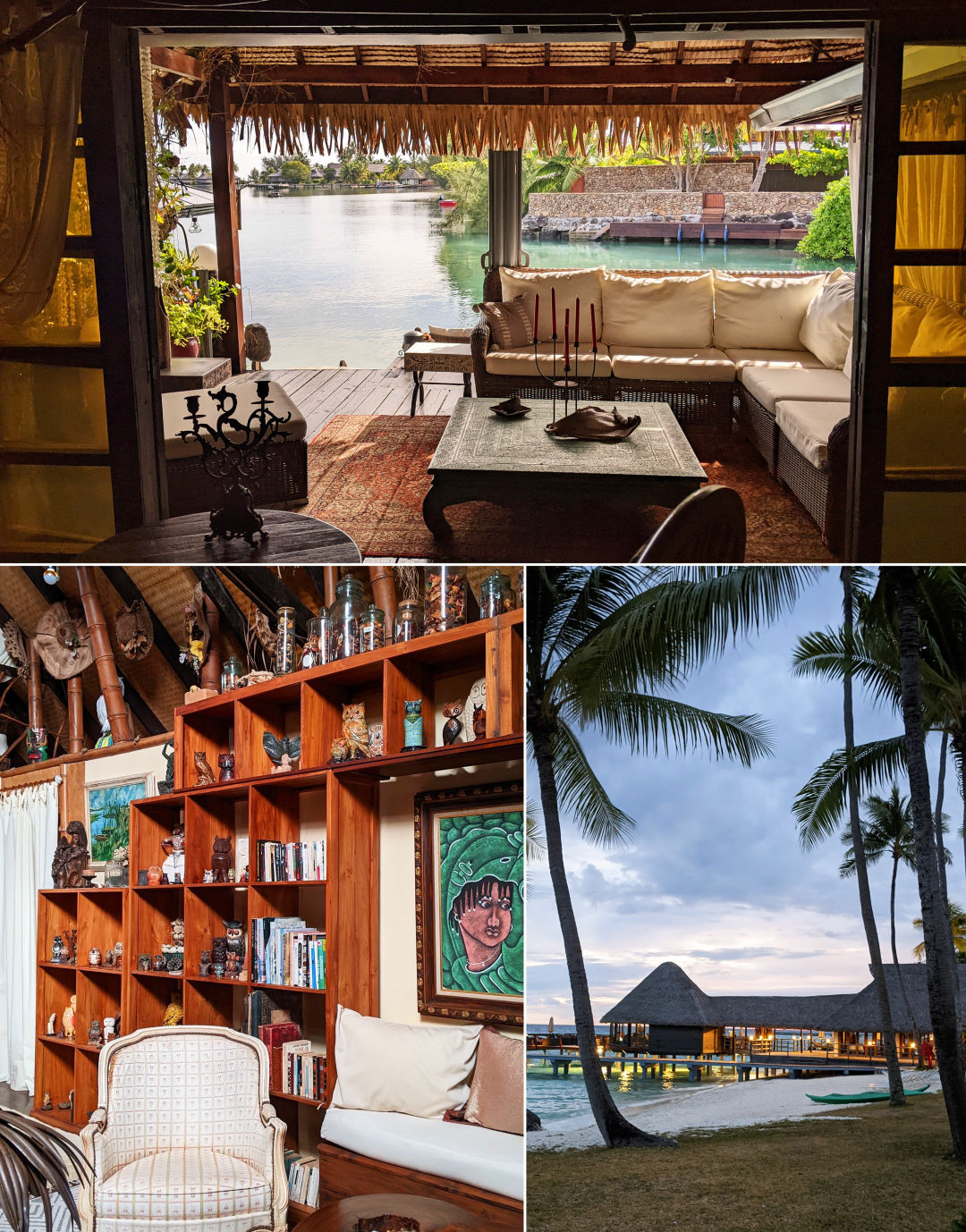

Antique European furniture sits under a thatched palm roof. A library lined with bookshelves and cascading greenery give way to a patio on a placid lagoon. Here in this tiny hotel on a relatively small island in the South Pacific, Polynesian art shares space with thick woven rugs that look straight out of an Oxford library. The whole thing feels like a tropical fever dream; squint and it could be 1890 up in here, where European colonial aesthetics are woven into a lush Polynesian landscape.

It's hot like Hawai'i, and blue waves crash just like they do in Hawai'i. Fresh mango and pineapple are sold at roadside stands, and locals saunter in flip flops year-round like they do in Hawai'i. But this artsy hotel, Fenua Mata'i'oa, is in French Polynesia, a country of 121 islands that sits south of the equator. Americans would call the whole nation Tahiti, but that's only the moniker of the central isle, home to capital city Papeete. This next-door island of Moorea has its own distinct feel, as do Bora Bora, Rangiroa, Fakarava, and any of the many islands favored by tourists—or the ones mostly ignored by outsiders.

We're in the same time zone as Honolulu, a fact repeatedly touted by Air Tahiti Nui when it launched a nonstop flight from Seattle to Papeete in 2022. That seems impossible until one consults a globe to see that French Polynesia is a kind of mirror image of the Hawaiian islands on the southern side of the equator.

But there's one major difference between a Hawaiian and a Polynesian vacation: sheer volume. Our 50th state saw more than 775,000 tourists in February 2023, while Tahiti got 15,000—which means more vacationers arrive in Hawai'i every day than French Polynesia sees all year. The immense distance from France, or any other population center for that matter, keeps numbers down—but the country is only a nine-and-a-half hour flight from Sea-Tac (about three hours longer than a jaunt to Oahu). With Hawai'i contemplating additional fees to help manage its massive influx of visitors, French Polynesia may be Seattle's sun-soaked alternative.

Like many hotels across the country, Fenua Mata'i'oa is owned by a French citizen who moved to the country's overseas territory, though what Eileen Bossuot-Surleau created on the north side of Moorea is so carefully curated that few Polynesian accommodations can match its idiosyncrasies. Chain hotels like Hilton and Sofitel dot the most popular islands, usually with overwater bungalows that have become a honeymooning staple. Smaller guest houses fill in the space in between, and on smaller islands like Huahine, Fakarava, and Rangiroa.

While capital city Papeete on Tahiti is famed for its giant central market, the island of Moorea is just 10 miles (and a ferry ride) away. The volcanic isle has steep mountains carpeted in greenery in the middle, but the skirt around the coast is flat and beachy, with an outer reef that keeps the big ways at a safe remove. From the Three Coconuts Lookout in the center of the island, the Polynesian classics all come into focus: thick jungle, topaz waters, and the busy clouds that form and dissipate with tropical swiftness.

Moorea's Fenua Mata'i'oa, top and bottom left, represents the island's funky side; a traditional resort like Rangiroa's Hotel Kia Ora, bottom right, embraces over-water living.

Image: Allison Williams

Bossuot-Surleau's quaint hotel operates more like a '90s joint—physical keys, phone communication. Visitors tend to laze about the place, given that there are more lounge chairs and reading nooks than rooms (just five), and harmless reef sharks circle the deck outside for easy snorkeling. Abandoned overwater bungalows from an old InterContinental Resort are visible down the shore, but this funky guesthouse endures.

The French colonized the Society Islands, one of five archipelagos that make up the current country, in the late 1800s, and that European influence is still deeply felt. At Rudy's, a longstanding Moorea restaurant, the proprietor is Tahitian-born but of French descent, and the menu lists boeuf bourguignon and rack of lamb. By far the most popular dish is a parrotfish stuffed with crab, the entire rich bundle coated in a tarragon sauce. It's the kind of dish you bookmark for a return trip. When we fail to hail a taxi on the way back to our hotel, a young French couple gives us a ride across the island while telling is why they left France to practice medicine in Polynesia (the adventure, basically).

But despite the colonial influence, Tahiti's Polynesian roots still define the country, part of a culture spread as far as the indigenous peoples of New Zealand (the Maori), Easter Island, Samoa, and, of course, Hawai'i. Even as street signs are written in French and the currency is labeled the franc, Polynesians far outnumber the European-born. And for the occasional frites and pizza, many more snack stands and hotel buffets serve the rich national dish of poisson cru, or raw fish in coconut milk.

Beyond the island of Tahiti, most Americans have heard of Bora Bora, an island used as a supply base by U.S. troops during World War II that later transformed into honeymooner central. But French Polynesia's less glamours gems lie a lot further afield, like in the range of atolls that lie in the Tuamotu archipelego to the east. (Internal airline Air Tahiti superimposes its route map over an outline of Europe to express scale—if Tahiti is Paris, these atolls would be somewhere around Antwerp. The country is wide enough to reach Stockholm and Sarajevo.)

Here the flat island of Rangiroa sits like a misshapen cookie cutter in the middle of the ocean, a spindly outline 50 miles wide with a lagoon in the center—one of the largest atolls in the world. The land is flat as Kansas but as little as 1,000 feet from the inner shore to the outer Pacific coast, the large ring occasionally broken by water passages.

Bikes are the easiest way around the isle; there really isn't anywhere to go. When Snack Chez Lili, a waterfront lunch restaurant, opens midday, it feels like the entire island descends for sashimi and lagoon fish drenched in curry sauce. On Rangiroa the seafaring bravery of the early Polynesian is more even mind-boggling, knowing they traveled by handmade boats between tiny specks of land with no fresh water sources on them.

Bottlenose dolphins seek out scuba divers at Rangiroa's Tiputa Pass.

Well, no fresh water source but the rain. With no landforms to hold up the clouds, weather travels swift across the ocean here, and periods of intense rainfall aren't uncommon. It would all be so disappointing to the sun-seeking vacationer if it weren't for what's under the surface. Rich coral reefs make for the kind of snorkeling that recalls Disney movies, with wiggly eels emerging between almost comically colorful anemones and fish.

And in Tiputa Pass, where currents push water between the ocean and the lagoon, bottlenose dolphins come to frolic in the resulting waves. They'll swim inches from scuba divers on their way to the playground, or even stop to twirl among the humans. Even as rain falls in sheets across the beaches it feels sunny underwater, in a way.

The French Polynesian blend—rustic yet accessible, local yet global—is foreign to most Americans, but immediately appealing. To a Pacific Northwesterner used to the vagaries of marine weather, this form of Pacific makes a certain kind of sense. A little hiking, a little swimming, then a little history and a little culture; fresh seafood, served simply. It may even sound familiar.