The Boat at the Bottom of the Sea

Illustration by Zach Meyer

Captain William Prout was up early. Or was it late? During crabbing season it was sometimes hard to tell the difference. The day before, Friday, February 10, 2017, Prout and his crew had offloaded a batch of snow crab on the remote Bering Sea island of St. Paul. Then they’d turned the Silver Spray around and motored back out to the fishing grounds to collect their remaining crab pots. At 5am on Saturday, Prout pulled his anchor and pointed his bow southeast.

Hours of darkness still remained—dawn came late on the Bering Sea in February. Captain Prout stayed in the wheelhouse, drinking coffee with his son and looking out at the icy night, as the Silver Spray churned along.

Sometime between 6:15 and 6:30am, he heard the first calls on the VHF radio: The Coast Guard was trying to reach another crabber, the Destination, on channel 16.

Channel 16 was dedicated to emergency communications, but Prout didn’t think much of the callouts at first. He figured maybe a safety device known as an EPIRB (emergency position-indicating radio beacon) had gone off by accident, and the Coast Guard was confirming the false alarm. But when the Coast Guard hailed the Silver Spray directly, asking Prout to try to reach the Destination—he called out to the boat several times without receiving a reply—he began to worry. He was roughly 20 miles from the Destination’s last known position: just north of the island of St. George. At 7am he altered his course and headed straight there.

More than a thousand miles away in Juneau, the staff at the Coast Guard’s District 17 command center prepared for the worst. The EPIRB is designed to activate when submerged in water, signaling that its ship is in serious distress. By 6:45am, when nobody could raise the Destination on the radio, the Coast Guard authorized a launch. A search-and-rescue plane was dispatched from its base on Kodiak Island, alongside a helicopter. A second helicopter also launched from the Coast Guard’s forward operating location in Cold Bay. The Coast Guard cutter Morgenthau, which roamed the Bering Sea year round, altered course to head to St. George as well. The distances involved were vast, but all of the Coast Guard’s assets in the region were converging on the location of the Destination’s signal.

The Silver Spray arrived around 9:30am. Captain Prout had switched on his boat’s big sodium lights, intended for night fishing, about 45 minutes earlier, and now he and his men started to see debris bobbing in the swells. Another boat that had been working nearby, the pollack trawler Bering Rose, was also searching the scene; they spotted fishing buoys, a bait jar, and an oil slick riding the waves.

The hum of a Coast Guard C-130 filled the air just after 10am. The sky was lightening now, and from their vantage point the airmen had sighted some floating objects that the men on the fishing boats couldn’t. By radio, they directed Prout and his vessel to move closer and retrieve them.

As they drew nearer, the crew of the Silver Spray could finally see what they were chasing, tossing on the surface of the dark water: a faded red life ring, with the words “F/V Destination” marked in black block letters, and the EPIRB itself: a yellow device the size of a Slurpee cup, attached to a bright coil of yellow rope. The men leaned over the ice-coated railing of their boat and reeled the items in with grappling hooks.

The Coast Guard’s search for the boat carried on throughout that day. The agency uses a program called SAROPS to predict where in the vastness of the ocean it needs to look. You input the last known location of a vessel in distress, and then SAROPS does the math, taking into account wind speeds, ocean currents, and other factors in the area in question, to divine where a given object—a life raft, say, or a man in a survival suit—might wind up. SAROPS also includes a feature called the Probability of Survival Decision Aid. Input a person’s height, weight, gender, and presumed clothing, and the program spits out a grim prediction of how long the person is likely to survive in the water. In a life raft, mariners might have 24 hours for the Coast Guard to find them. In a survival suit, in Alaska, that number drops below four hours. In street clothes? Minutes.

On the island’s windswept, treeless shore, a few St. George locals scoured the waterline for more debris or any sign of survivors. The aircraft, meanwhile, focused on a hunt for the life raft. Boats like the Destination carry inflatable emergency units equipped with a hydrostatic release, triggered—like the EPIRB—by immersion. When its ship sinks, the life raft should pop loose automatically, inflating and rising to the surface. That means any crew member who makes it out of the sealed confines of the boat will have a lifeline waiting for them. But even with the drift modeling, the searchers on shore, the aircraft in the skies, and the Good Samaritan vessels in the water, the Destination’s life raft was nowhere to be found.

The Seattle-based commercial crabber F/V Destination in Bristol Bay, Alaska, July 2015.

Image: Capt. Jack Molan

Here is what we know for sure: The F/V Destination, a U.S.-flagged, Texas-built, Seattle-based commercial fishing boat, sailed from the port of Dutch Harbor, in Alaska’s Aleutian Islands, just after 11pm on Thursday, February 9, 2017. There were six men on board—the captain, Jeff Hathaway, and five crew: Charles “Glenn” Jones, Raymond Vincler, Darrik Seibold, Larry O’Grady, and Kai Hamik.

The men were more than colleagues; they would often refer to themselves as a family. (“Jeff was Dad,” a former crew member once joked.) Captain Hathaway, who was born in Tacoma and grew up in Seattle’s Magnolia neighborhood, had been running the Destination since 1993. O’Grady, of Poulsbo, had been on board for nearly as long. Darrik Seibold, raised in both Southeast Alaska and Olympia, inherited his spot on board from his younger brother Dylan. And Kai Hamik, a friend of Dylan’s, had joined the crew in 2011, when he was just 24; his father had fished salmon with Hathaway years earlier.

We know that Hathaway, 60, once threw an orange at a producer from Deadliest Catch—his way of saying: I don’t do reality TV. He was a camper, hiker, skier, and cards player, and an active participant in the Seattle Times’s Mariners online forum. He and his wife, Sue, had one daughter, Hannah, who grew up riding horses on the family’s Port Orchard ranch. (One year, when his daughter rode in the Bremerton Armed Forces Day Parade, Hathaway wound up on poop-scooping duty, following behind the horses with a wheelbarrow and shovel, and just laughed off the razzing he got from the crowd.) He liked to grow tomato plants in the summers, and he inspired Hannah to do the same. On February 9, 2017, before leaving Dutch Harbor, he talked with her by phone and encouraged her to get her plants started for the year. She went out and bought a pack of seeds the next day.

We know that Darrik Seibold, 36, was a tinkerer and an artist. He’d taken top prizes in grade school art competitions, and as he grew up he continued to love working with his hands: sketching, painting, building. He filled his mother’s basement with inventions. He worked construction in Olympia, Juneau, and Phoenix. He taught himself about AutoCAD, architecture, electrical work. Later he had a son, Eli, who became the center of his world. Eli had his third birthday one week after the Destination disappeared.

We know that Kai Hamik, 29, had spent his childhood summers in southwestern Alaska often beachcombing with friends. His parents had split time between Arizona and Alaska, but when he and his sister, Leilani, reached junior high, the family moved to the desert year round. Still, Kai was drawn back to the ocean: By the ninth grade, he was fishing for salmon every summer in Alaska, and within a decade after that, he was crabbing. When he was home, he and his girlfriend would dive fearlessly into home renovations and building projects. Still Arizona based, they were looking for land to build on in the Seattle area. (Captain Hathaway had offered to sell them a parcel of his ranch.) Kai was independent, and funny: Admonished by his mother not to buy a Harley Davidson, Hamik bought a dog instead—and named it Harley. Later, he bought the bike, too.

We know that when he wasn’t out in the Bering Sea crabbing, Larry O’Grady, 55, could often be found…fishing. He’d fish for salmon in the summers, he’d seek out dungeness crab closer to home, he’d put out shrimp pots in front of his house on the Olympic Peninsula. He joked that splitting wood in the yard was his “therapy.” He met his wife, Gail, on a blind date more than three decades ago: He picked her up in a limo, and they moved in together two weeks later. They got married in Hawaii, at a place called Shipwreck Beach.

We know that no one can seem to find any surviving photographs of the men of the Destination smiling for the camera together. The pictures were all on the boat.

The six men had just wrapped up their cod-fishing season and were now getting set to fish for what is commonly known as opilio—Chionoecetes opilio, or snow crab. Alaskan crab fishing, made notorious in the wider world by the reality TV show Deadliest Catch, involves setting out heavy steel traps, called pots, on the ends of long lines attached to buoys. The pots, each of which can weigh 700 pounds or more, are loaded with bait and lowered by crane into the ocean. They’re designed so that crabs can enter, in search of the bait, but can’t leave. The crabber returns, the crew retrieves each pot and buoy and loads the boat’s fish holds with their catch, and the process begins all over again.

In Dutch Harbor, the crew of the Destination had picked up an extra load of bait for their 200 crab pots, bringing the total on board to 10,000 pounds. Hathaway wouldn’t ordinarily carry that much bait for a single fishing trip; ideally, he’d complete a round of fishing, then buy additional bait at the Trident Seafoods facility on St. Paul, the island well north of the main Aleutian chain, before heading out again. But he’d been warned that there was a shortage of bait on the island, so he’d stocked up in Dutch Harbor instead.

Ice is a common threat to crabbers who fish in the Bering Sea in the winter.

The Thursday weather forecast for St. Paul and St. George, the two adjacent islands, included a heavy freezing-spray warning throughout Friday night. In the southern Bering Sea in winter, the vast mass of the ocean can remain unfrozen, even as temperatures plunge well below freezing. But where the saltwater is broken apart and flung into the air by wind and waves, it loses its immunity to the cold and it freezes fast to any surface it touches. The crabbers that fish the Bering in winter measure the accumulation of frozen spray that clings to their vessels by the inch. It locks onto their hulls, to any gear on deck, to the bars of steel and strands of webbing in their crab pots. It can coat the life rafts, and it can block the freeing ports—the cutouts in the boat’s bulwarks that allow large waves to wash over and through rather than trapping them on deck. Crab boats, loaded with stacks of pots, are relatively top heavy to begin with, and enough ice buildup can overload them. The crews battle the ice with mallets, crowbars, and—in the old days, at least—baseball bats.

From a ship tracking system, AIS, we know that by the early hours of Saturday, February 11, the Destination had reached the southern shore of St. George Island and chugged up its western side. By 6am, the boat cleared the point on the island’s northwest corner and was back in open water, heading for St. Paul.

At 6:14am, the boat’s AIS tracker stopped transmitting. And at 6:15am, the EPIRB went off.

Two and a half days after that, following a fruitless search, the Coast Guard declared the Destination and the six men on board lost at sea.

At a memorial service held a few weeks later in Shoreline, a pastor read some prepared remarks from the Destination’s owner, Edmonds-based David Wilson. “God only knows why something like this happens,” Wilson wrote. “I don’t know why these good men went down at sea.” It was true. No one knew what went wrong—and so quickly that the crew couldn’t even get out a mayday.

Off the Map

The final path of the Destination. It emitted its last-known signal just off St. George Island at 6:14am, Saturday, February 11, 2017.

On February 17, six days after the loss of the Destination, the Coast Guard announced it was convening a Marine Board of Investigation—its highest and most formal level of investigative process—in order to determine, if at all possible, the cause or causes of the sinking. The board would also make recommendations aimed at preventing other boats in the crabbing fleet from facing the same fate. The chairman of the board was commander Scott Muller, the chief of inspections and investigations at the Coast Guard Fifth District, based in Portsmouth, Virginia.

Muller cut his teeth in Tampa doing investigations on parasailing mishaps, among other incidents. It was there that he became fascinated by human error, and the ways in which humans and machines collide in emergencies at sea. After a graduate degree on that theme, he did a stint in Mobile, Alabama, as the chief of the prevention department, before landing back in Virginia in his current role. The Marine Board of Investigation is a tool that is rarely deployed by the Coast Guard; chairing one, for Muller, was a once-in-a-career opportunity.

In the foreword to his best-selling book The Perfect Storm, about the loss of the swordfishing boat Andrea Gail in a hundred-year storm off Nova Scotia, Sebastian Junger writes: “I’ve written as complete an account as possible of something that can never be fully known.” That was the task facing Commander Muller and his team—to piece together the narrative of an accident with no surviving witnesses, no boat to examine, no mayday calls, and no clear indication of what went wrong.

They would attempt a kind of mathematical detective work. By following a paper trail and interviewing witnesses, they would fill in as many variables as possible—the weather during the Destination’s final voyage, the boat’s state of repair, the weight of the crab pots and bait on board, the habits and routines of the crew, and much more—in order to complete an elaborate equation. Solve for X—X being the probable cause of the sinking.

Back in February 2017, Muller had assembled his team and begun his research. In late March he flew to Seattle, and then on to Anchorage and Dutch Harbor. He spoke with Coast Guard officials everywhere he went, learning everything he could about the regulatory regime the agency applies to commercial fishing vessels in the Bering Sea. He met with Wilson, the Destination’s owner, in Seattle, and in Dutch Harbor he toured a working crabber. He sought out anyone who’d had contact with the Destination in the weeks leading up to its final voyage. He learned about the boat’s maintenance record. He immersed himself in the unique and dangerous world of Bering Sea crab fishing.

The investigation’s formal hearings were scheduled for the second and third weeks of August, in Seattle. Although the sinking had occurred in Alaska, most of the crew and their families, and many of the investigation’s witnesses, were based in and around Puget Sound. Holding the hearings here was a logistical decision, but it was also fitting: Much of the crabbing fleet is like an extension of greater Seattle, an annex in the Bering Sea.

In late April 2017, some three months after the Destination disappeared, a research ship belonging to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration was scheduled to be in the Bering Sea. At the Coast Guard’s request, the crew of the Oscar Dyson detoured over to the lost crabber’s final known location.

The Oscar Dyson, based in Kodiak, is intended for fisheries research, and its echo-sounding technology is tuned to seek out biomass in the water column rather than to map the seafloor. But its crew knew they had to at least try to find what they could. They focused their instruments on the ocean bottom and went to work, “mowing the lawn,” as they call it, in long sweeping lines, back and forth over the ocean just north of St. George. They were not able to determine whether the missing boat lay below.

Just over two months later another NOAA ship, the Fairweather, was traveling to Nome, on Alaska’s northwest Bering Sea coast. It, too, took a detour at the Coast Guard’s request. The Fairweather is a hydrographic survey vessel, equipped specifically for seafloor mapping, and after its arrival on July 8, its crew established a search area. They based their plans on the currents around St. George, the strong winds out of the northeast on the night of the sinking, the last blip on the AIS tracker, and the location of the EPIRB alert. Their search grid overlapped in part with the Oscar Dyson’s, but it also extended further to the east, north, and south.

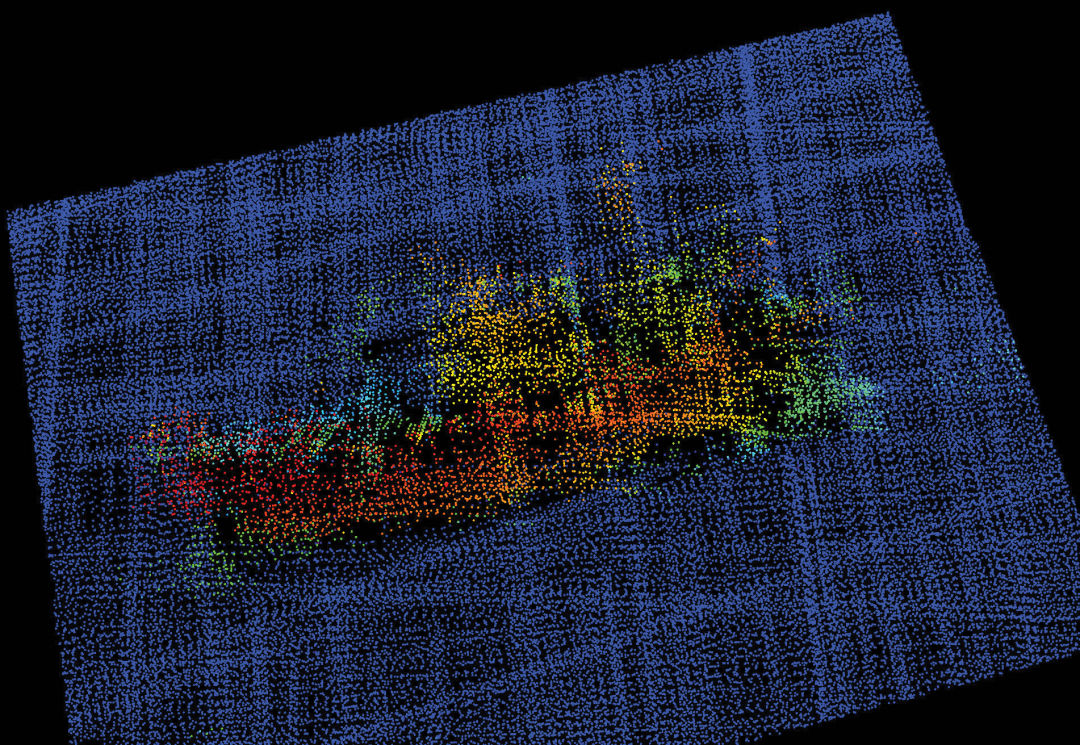

They were working their way north when the Fairweather’s sonar located an aberration on the ocean floor. Gradually the grainy images from the sonar came into focus: A boat sat on the bottom, 256 feet down, lying on its port side. A long line extended southwest from the boat, like a skid mark on the ocean floor, and beyond it, another blip in the usual seafloor pattern—something that looked like it might just be a pile of crab pots.

The images of the boat on the ocean bottom matched the shadowy, sepia-toned quality of an ultrasound photo. Like an ultrasound, they offered a tantalizing hint, a glimpse of something beyond our reach. The Destination had been found.

A NOAA research ship captured a sonar image of the Destination 256 feet below the ocean surface.

Image: Courtesy NOAA

The Marine Board of Investigation’s public hearings began promptly on the morning of August 7. Seattle was still caught in the grips of a heat wave and smothered by smoke from a series of regional forest fires. Outside the Henry M. Jackson Federal Building, at Madison and Second Avenue downtown, gulls screamed, a man sang loudly, and the usual antiwar protesters held their placards in the hot, thick murk. The air-conditioning of a large assembly room offered relief.

The room was filled with tidy rows of tables and chairs. At the front, the tables reserved for family members of the lost men were marked with Kleenex boxes, ready and waiting. A raised table faced the room, flanked by two flags: the Stars and Stripes, yellow fringed, and the flag of the United States Coast Guard. As the members of the Marine Board of Investigation settled into their seats, local TV reporters fussed with cables and cords at the back of the room. Commander Muller, broad shouldered and shaven headed, in a spotless dark blue uniform, gave a brief opening statement.

After the formalities, the first witness called to testify before the board was David Wilson. He sat down at the witness table and read briefly from a prepared statement. “The loss of my friends Jeff and Larry,” he said quietly into a microphone, “as well as the exceptional crew members of the Destination is a reality that haunts me every day.”

Wilson’s testimony carried on throughout the afternoon. But it left as many questions as answers. He didn’t know whether Captain Hathaway had received any formal training in vessel stability, and he didn’t know how many pots the crew would have loaded on board, or in what configuration. Yes, he had passed the message to Hathaway from Trident Seafoods, telling him to “bring a lot of bait,” but no, he couldn’t speak to why, exactly, Trident had made that request. (Through his lawyer, Wilson declined a request to be interviewed for this story.)

Following Wilson came three former Destination crew members, and then a handful of technical experts: naval architects and boatbuilders, people who’d worked on the boat over the years. There were Coast Guard officials responsible for fishing vessel inspections and safety programs; there were staffers from several Bering Sea seafood processing and cold-storage facilities. Later, the focus tightened further, onto the Destination’s final voyage, with testimony from the captains of the other boats that were nearby, from the National Weather Service on how freezing-spray warnings were produced and distributed, and, finally, from the NOAA and Coast Guard teams that had eventually located the sunken vessel on the ocean floor.

Some of the questioning, to an outsider, would seem almost absurdly specific. Some of the behind-the-scenes work would, too. Muller’s team needed to know, for example, how big the Destination’s freeing ports, those slots that allow seawater to escape, had been. But they lacked any formal drawings or plans of the boat’s layout—neither the owner nor the architects retained a copy. The team did, however, have a photo of the boat, its freeing ports in clear view, tied up at a Seattle pier. So Muller asked a Coast Guard staffer to go out to the pier and measure the stanchion in the foreground of one of the photos. From there it was a matter of doing the math.

Coast Guard aircraft typically search using a grid pattern. Commander Muller, in his own search, was instead working from the outside in, traveling in a tightening spiral that centered on the sinking. When a foreign object plunges into calm water, its impact ripples outward in concentric circles on the surface. The investigation was following those ripples back to their source.

The Evidence

Would-be rescue vessels uncovered items floating on the surface of the Bering Sea

Fig. 1 Buoys found near the missing ship’s last known location. Fig. 2 Life ring belonging to the F/V Destination. Fig. 3 The Emergency Position-Indicating Radio Beacon (EPIRB).

On the Friday of the first week, the investigation heard from witnesses about the Destination’s bait supply. The discussion was straightforward, even dry—the team scrutinized receipts and invoices, talked quotas and pricing. But then the investigators called up a video on the projector screen at the front of the room: a jerky, low-resolution time lapse recorded in Dutch Harbor. Kloosterboer Cold Storage’s dockside security cameras captured the Destination arriving, loading its bait, and departing.

At first, the questioning continued while the video played in the background. But its effect on the room was electric, and soon everyone quieted. One woman in the front row began to cry, shoulders shaking. Darrik Seibold’s brother Dylan leaned forward in his seat, watching intently. Kai Hamik’s father, Tom, stood up for a better view. On screen, the boat pulled up to the dock and was met by the Kloosterboer crew. A forklift appeared from out of frame, bearing pallets of bait, and the Destination’s small crane jerked back and forth in rapid motion, hoisting them aboard. The specks of the men were just visible on deck, moving antlike around the bow, preparing to cast off.

The Destination reversed out of its parking spot stern first and moved away, shrinking with each jump from frame to frame. The boat turned, began driving forward, and disappeared off the left side of the screen. The video—the last known footage of the six men alive—ended, and the hearing room was left in silence.

The families’ grief and loss were always a current moving invisibly under the surface of the hearings, but in moments like that, they became a tall swell, impossible to ignore.

There were other hidden currents present, too—themes that emerged from the testimony. The 2005 implementation of a new fisheries management system known as crab rationalization hung over the proceedings. The change was supposed to represent a hard shift away from the old derby-style crab fishery, a literal race to see which boat could catch the most crab the fastest, to a regimented system of allocated quotas and shares. Rationalization had radically shrunk the fleet, lengthened the crabbing season, and changed the industry, stabilizing the system and leaving more power in the hands of the quota holders. It had also, according to at least one witness, failed to alleviate the time pressures that the men on the boats labored under, and left a wider gap between haves and have-nots.

Darrik Seibold (right) and his brother Dylan Hatfield aboard the Destination.

Image: Courtesy Dylan Hatfield

Dylan Hatfield, Seibold’s brother, was the lone family member to testify. He did so in his capacity as a former crew member on board the Destination, and after his questioning was over, he had something to add. There was a disconnect, he felt, postrationalization, between the owners and their crews. “I feel like those are your biggest pressures in the industry: quota holders, boat owners, and market delivery dates,” he said. “I think that the race for fish needs to come to an end…. Why are we working 40-hour days? What’s the race? Why are we racing for fish still?”

Hatfield spoke forcefully, the words rushing out of him. “We’re out there breaking our backs, beating ice, going out in 40-, 50-, 60-knot winds, for what? For what? So that the guy on the beach can get a check a couple weeks sooner?”

The question of catch delivery dates was one that Muller and his team circled back to again and again. Asked what the consequences of a late delivery would be, David Wilson testified that since his boat had never missed a delivery, he was unaware of what might result. But Ricky Fehst, the captain of the April Lane, had watched the Destination, loaded with pots, sail out of Dutch Harbor and had worried at the time, given the warning of heavy freezing spray. “It seems to me like he was under some kind of pressure, of some sort, to leave town during this forecast,” Fehst said. He added: “We shouldn’t have to do this anymore.”

Deadline pressure alone can’t sink a ship, though, and there were other recurring topics in the days of testimony. There was the missing life raft: Had its release mechanism failed? Had the crew been experiencing some kind of mechanical difficulties? There was the matter of the boat’s sporadic steering issues, in the past, when the rudder would suddenly lock up and go hard over to one side. The problem had, in theory, been resolved by summer maintenance.

There were repeated questions about the weight of the Destination’s crab pots. The boat’s stability guidelines were based on the assumption that each pot, with line and buoy inside, weighed 725 pounds. David Wilson guessed that his boat’s crab pots likely weighed around 700 pounds each, and other mariners who testified agreed with that rough figure. But in the second week of hearings, a Coast Guard official, Jack Kemmerer, introduced the concept of weight creep: the gradual, unacknowledged increase in the weight of gear, which could accumulate over time—and eventually, potentially, affect a vessel’s stability.

On the last day of the hearings, Muller heard testimony from a Coast Guard team that had just, days earlier, visited the site of the sinking. After the NOAA ship Fairweather had located the probable wreck of the Destination, the Coast Guard icebreaker Healy had detoured to St. George, too, and its crew had managed to retrieve a crab pot and its gear from the ocean floor. The boat had given up one of its mysteries, at least. The pot weighed in at 880 pounds, nearly 200 pounds more than estimated.

By the end of the hearings a probable picture had emerged—still fuzzy around the edges, still hypothetical, but you could make out its shape in broad strokes. On February 10, 2017, the Destination was a boat in a hurry, fully loaded—perhaps, unknowingly, even overloaded—as it headed into a night of nasty weather. As morning came on, and the boat rounded the northwest corner of St. George, leaving the lee of the island, it would likely have been iced up, maybe already listing slightly to its starboard side. Its exact condition at that moment—its configuration of crab pots, its load of bait, its route and destination—was the result of dozens, even hundreds of disparate factors. Commander Muller’s final report and recommendations, when complete and released to the public, will aim to prevent that combination of factors from ever recurring.

Jeff Hathaway and his daughter, Hannah Cassara, on the Destination in the 1990s.

Image: Courtesy Hannah Cassara

At the Seattle Fishermen’s Memorial, on the shore of the Lake Washington Ship Canal, names etched in bronze date back to 1900. They’re organized by decade, row after row of them, on metal plaques fixed to low stone walls. The walls sit around a tall plinth topped by a sculpture of a man holding a fish on a line. Among the most recent additions are the names of the men of the Destination: Kai J. Hamik, Jeffrey A. Hathaway, Charles “Glenn” Jones, Larry O’Grady, Darrik Monroe Seibold, and Raymond James Vincler.

In front of the formal memorial are the informal tributes that come and go with time. In August, as the city sweated and the hearings rolled on, that meant six tall cans of Budweiser, one for each crew member. A child’s painting of a crab, made from two small handprints joined at the wrists. A potted plant labeled “a tomato plant for Jeff.” And, from Hathaway’s wife, Sue, a verse echoing the laments of centuries of loved ones: “There’s only one man for me, and now he belongs to the Bering Sea.”

The Seattle Fishermen’s Memorial on the Lake Washington Ship Canal.

Image: Courtesy Dylan Hatfield

In February 2018, on the one-year anniversary of the Destination’s sinking, several family members and loved ones of the lost men headed out on Puget Sound for a sunset cruise together. They’re all still trying to wrap their heads around a loss that remains incomprehensible. Gail O’Grady, Larry’s wife, was able to hang onto their home in Poulsbo, but it’s a lonely place for her now. Dylan Hatfield sometimes struggles with the knowledge that he helped Kai and Darrik land their spots on board the boat. Tom Hamik hopes he can eventually get to the point where thinking of Kai summons a smile, instead of the haunting image of his son taking his last breath. Some days, he feels like he’s starting to get there.

Hannah, Jeff’s daughter, never managed to plant those seeds that she’d bought last year, the day before the sinking. But this spring, she got her garden started again. Her toddler, who called Hathaway “Pa,” sometimes helps her water the tomato plants. She likes to say that they’re growing Pa’s tomatoes.

Updated April 10, 2018. This version names Kai Hamik’s sister, Leilani.